Shams Ur Rehman Alavi

In mid-1980s, there used to be a column in children’s magazine, Paraag, where the editor replied to readers’ queries in detail, but also tried to bring a little humour.

I remember, once a boy had asked, ‘Uncle, why an intelligent person is called ‘aql-mand’ when ‘mand’ means slow in Hindi?. The editor, Kanhaiya Lal Nandan replied, ‘My dear son, it’s Farsi suffix ‘mand’ and by not realising it, you are proving yourself ‘aqal’-‘band’ [mind closed, shut].

The boy was curious, rightly so, because nobody tells that this is Persian, which was for centuries the language of courts and administration in India. In fact, there is so much Farsi in vocabulary in Indian languages that it is an intrinsic part of lingua franca but people don’t even realise it.

From words as small as ‘daar’ [keep, hold], or ‘khaana’ [house] or ‘mand’ [having], each forming hundreds of words — dukaandaar [shopkeeper], dawakhaana [dispensary or medical shop], ehsaanmand [indebted], it is so much present in our speech — even if a person is speaking Urdu, Bangla, Hindi or Marathi, that it is not even noticed.

In 1980s, when I was a young boy, I was expected to learn Farsi, in order to improve my Urdu. I wasn’t too interested but elders would always insist that without Farsi, you can never have good command over Urdu.

My mother felt that if I learnt a bit, I could be able to relate to ‘tough Urdu’ that was written in the past and also understand the poetry of Maulana Rom [Rumi], Urfi, Nazeeri and Hafiz, that her elders often quoted.

For me, the idea that one had to take out time in the summer holidays and spend time on yet another subject, was strange. After all, one barely got two months of summer holidays, and the thought that you have to spend an hour or two out every day from the schedule, was not delightful. Still, I had no choice.

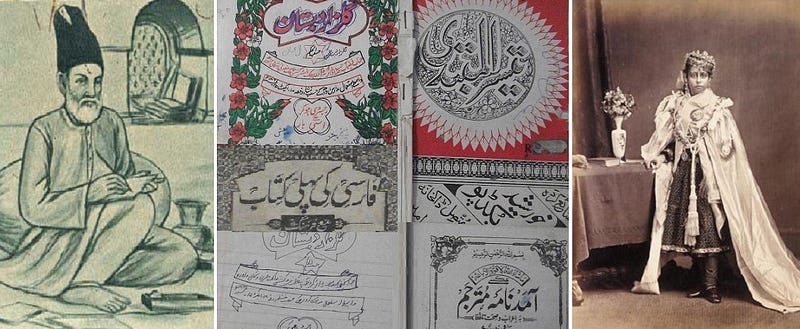

Some of my uncles suggested that I should start with ‘aamad-nama’. However, one of my elder cousin brother, Ahmad Yahya bhai, gifted me Tasir-ul-Mubtadi.

But, when I started, it was the traditional way — rote learning, repeating the ‘sabaq’ in Gulzar-i-Dabsitaa.n that for centuries has been the standard basic text for beginners in the sub-continent.

Many of my friends and young friends in UP, Bihar or other states who had the option to study Persian as third language in certain schools, had ‘the first, second, third book of Persian for each class’.

However, I had to repeat terms ‘Aab-e-Zar’ — Soney Ka Paani, Aawaz-e-Dilkash — Dil ko kheenchne wali aawaaz, Peer-e-Kham-Kamar — Tirchhi kamar wala boodha, initially.

It was a system of training the mind, so that you directly learnt the language — entire sentences and could make out the meaning, without getting lost into the complex maze of tenses and the rules of grammar.

I must say that Hafiz Shah Taqi Anwer, the renowned scholar, gave me ample attention and taught well. In addition to reading and repeating, I had to write it on ‘takhti’ with the reed ‘qalam’.

This routine continued for a few years. Must be around 40–50 classes every year in the summer holidays when I visited Lucknow. Unfortunately, I couldn’t go past all the ‘hikaayaats’ [moral stories in prose form] in Gulzar-i-Dabistaa.n.

Today as I look back, I feel I should have an opportunity to study it in school as well. However, I got a basic understanding, which indeed helped me in Urdu. The Gulistaa.n and Bostaa.n were read more as a tradition, later on.

India has produced huge literature in Persian. Almost every library in old parts of a prominent Indian city or town has racks filled with Persian books. There is also so much religious literature in the form of classical texts.

And above all, the appeal of poets like Hafez and Rumi, that is unparalleled. Urdu ghazal is an extension of the tradition of Persian poetry. Mirza Ghalib was immensely proud of his Persian poetry. He wrote:

Farsi ba-ee.n ta-ba-beeni-naqsh-haai-rang rang

Baguzar az majmua-e-Urdu ke be-rang man-ast

He felt there was an immensely beautiful world in his Persian poetry, compared to his Urdu works that he found ‘colourless’. Unfortunately, he is loved and known more for his Urdu poetry that he didn’t take too seriously.

One of the greatest Persian poets, Bedil, is buried in Delhi and Sheikh Ali Hazee.n in Benares. Till just over a decade ago, veteran poets like Saraswati Saran Kaif in Bhopal and Qasim Niyazi were actively penning Farsi poetry.

In Bhopal, the city I grew up, there were many Persian scholars. It was once a princely state and Persian was the state language till 1858, until it was replaced by Urdu. Nawab Shahjahan Begum was an accomplished poet who has a collection of poetry in Persian too.

Three hundred and fifty miles away, Lucknow too remains a major centre of Persian. Wali-ul-Haq Ansari continued to write poetry in Lucknow till the last decade.

People learn the language in households or from elders. Besides, Persian is taught in madarsas and Darul Ulooms and there are Persian departments in umpteen Colleges and Universities. It is also taught in Islamic centres, Sufi darsgaahs and Khanqaahs.

Lot of people learn it as it considered part of culture, along with Arabic and Urdu or those who appreciate the Farsi shaa’eri [poetry].One of the challenges faced in learning Persian is that we still learn classical Persian in India and there is a disconnect with modern Persian.

There is need for better books and smarter ways. Especially, the use of audio-visual medium to teach so that students learn the correct pronunciation, because even otherwise there is a tendency to shun ‘eraab’ i.e. ‘zer-zabar-pesh’ [maatras] in printing Urdu, Persian books.

READ: Once language of court and administration, Farsi survives in the country in a unique way